Ontario firm’s spill recovery innovation challenges status quo

David Nesseth

When government and industry won’t embrace technological innovation, where do inventors like Imbibitive Technologies turn?

WELLAND,Ont.—John Brinkman says he’s often greeted with a cynicism reserved for snake oil salesmen. Oil folk, he knows, are difficult to impress. Over the last 30 years, they’ve seen it all—an assemblage of products that simply don’t do much in the way of actually cleaning up an emergency spill.

“We get lumped in with everyone else. People think, ‘here comes another snake oil salesman.’ But then it turns out to be better than sliced bread,” says Brinkman, president of Imbibitive Technologies Canada Inc.

Learning about the spill business, Brinkman quickly found that North American companies have no required performance standards for the clean up of a hazardous and noxious substance spill, apart from voluntary standards. He wondered how people knew just how well, or more importantly, how poorly, a spill’s contaminants were recovered. Throughout history, the fact that a spill is ever even “cleaned-up” is generally considered enough, he says. And for good reason. For most of the world’s industrial history—rife with secret dumping and unreported spills—just getting to that point was a struggle.

Standard operating procedure at a spill seemingly topped out at evacuating the “hot zone” and letting Mother Nature deal with the rest, says Brinkman. The industry lingo for the end of a spill cleanup is called the “treatment endpoint.”

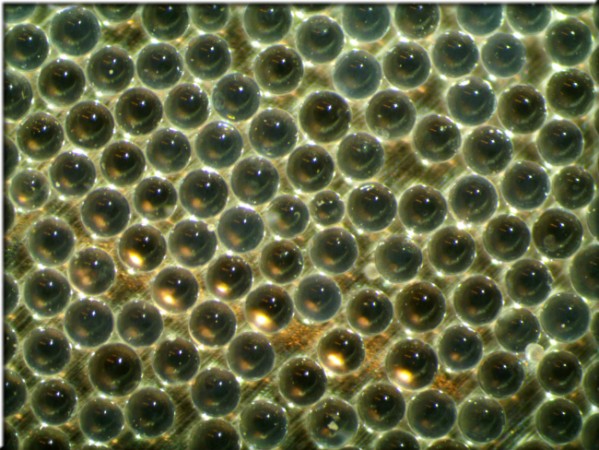

Fast forward to 1994, when Brinkman began Imbibitive Technologies. With the devastation of the 1989 Exxon Valdez Alaskan oil spill still fresh in mind, he figured his company’s revolutionary spill control product, IMBIBER BEADS®, would change the market, making poor contaminant recovery rates at disaster cleanups a thing of the past. Innovative as they were, the Imbiber Beads concept was simple; so simple, it’s based on baby diaper technology: Place the small plastic beads into contaminated water, and watch them expand, absorbing (or imbibing) some 27 times their own volume, essentially solidifying the liquid contaminant, making it part of the IMBIBER BEADS molecular structure. [See video at bottom of page.]

But the spill revolution never happened. Sixteen years later, says Brinkman, “[BP] Deepwater Horizon hit,” and it was “the same lousy techniques,” and the same poor performance, he says. Only a small fraction (anywhere from three to 25 per cent) of the oil from Deepwater was actually recovered during the clean up process. Then, “desperation called for desperate measures,” he recalls. “They dumped detergent on the oil [at the broken well-head] for the first time in history without knowing the long-term effects,” he says, referring to the use of Corexit oil dispersant.

What was going on? Brinkman wondered. His product is easy to use and could reach contaminant recovery levels of up to 90 per cent. The industry standard for recovery ranges from five to 15 per cent.

“The knock against IMBIBER BEADS has always been ‘great product, too expensive.’ But too expensive compared to what?” asks Brinkman. Too expensive to actually clean-up contamination? It’s not expensive when companies are paying less for a product that doesn’t really work, he says. “They’re good at buying equipment, using it, and not recovering. The industry has built itself up by being ineffective.”

But Brinkman’s still championing his flagship product, and hoping that industry and government will finally realize that it’s time to start doing better, to start hitting respectable recovery levels at cleanups, instead of just showing up and getting paid with little accountability.

IMBIBER BEADS technology is based on the super-absorbent invention of Pampers, the popular polymer baby diaper developed by Victor Mills in the 1960s. Dr. Richard Hall, a Dow Chemical Company researcher, and Brinkman’s late partner, developed IMBIBER BEADS by expanding on Hall’s work. A team of four full-time researchers, formerly of Dow Chemical, are working passionately on new variations of IMBIBER BEADS, such as a smaller version and a liquid version. The team is also developing a bead that will perform more effectively for spills that involve heavier substances like refined oil.

Now, the Welland, Ontario-based company, with two locations in the United States, spends a lot of its time educating industry and the public about reaching higher spill recovery levels.

“It’s a labour of love, and a commitment to change things for an industry that hasn’t done well, but is still walking the walk,” says Brinkman.

While North America has been tougher to crack, with more established, cheaper clean-up practices leading the way, IMBIBER BEADS has found success overseas, where Brinkman has experienced more “open-mindedness.” In Japan, for example, the Japanese Coast Guard and the Maritime Disaster Prevention Centre from Yokohama undertook years of testing to find the most effective spill containment technology. They chose IMBIBER BEADS, which is also starting to find success in Africa, too. A summer 2014 deal with Adventium Global Inc. will see IMBIBER BEADS used in 13 African markets.

In North America, meanwhile, particularly Canada, Brinkman has become somewhat disenfranchised dealing with Canadian officials. Industry, too, has been slow to respond, but the wheels are still moving. He’s disappointed, however, because he wants Canada to perform better, reach higher. It’s where he lives, but unfortunately not who he often ends up doing business with.

“We have to go offshore to prove our technology,” says Brinkman, who views North American legislation with some caution. “Industry had a heavy hand in writing these regulations,” he notes. But his real concern is with the lack of enforcement.

Environment Canada published a document in 2007 that lays out some strategies about how to determine when a spill cleanup is finished, the crew having reached the treatment endpoint. But there still remains an absence of spill recovery benchmarking.

“Environment Canada recognizes that each oil spill response requires a tailored set of criteria to determine when spill cleanup should end,” says the department’s media relations advisor Danny Kingsberry. “These criteria—called clean-up endpoints—are developed by considering the human and ecological uses of the areas affected by the spill, and the needs of the populations who live in and depend on these areas. The decision of when to cease spill clean-up operations and what monitoring should be undertaken post-spill is made based on a net environmental benefit process, in consultation with local stakeholder groups. These groups include local and provincial governments, First Nations communities, as well as other federal agencies and departments, including the Canadian Coast Guard and the Department of Fisheries and Oceans.”

Most commercially available spill clean-up products on the market are surface-coating materials and are considered under ASTM International Performance Standard definitions to be adsorbent instead of absorbent. Through use of an adsorbent, the contamination essentially adheres to the clean-up product, whereas an absorbent product, like IMBIBER BEADS, sucks up the contaminant into the clean-up product.

IMBIBER BEADS technology often gets lumped in with clay and polypropylene clean-up products, says Brinkman.

While Imbibitive Technologies continues to enjoy success with its other product lines, Imbiber Beads still remains its flagship product, mostly because of the huge potential is has to help the environment.

Moving forward, Brinkman is building support from environmental advocacy groups like the Riverkeepers. He’s just hoping the support ramps up to the point that North American industry will sit up, respond, and take spill recovery technology into the 21st century, exactly where he says the environment needs it to be.