NAFTA: Tug of war unfolding over concluding a quick deal

by Alexander Panetta, The Canadian Press

All three NAFTA countries insist they're prepared to keep talking, but it's unclear for how long

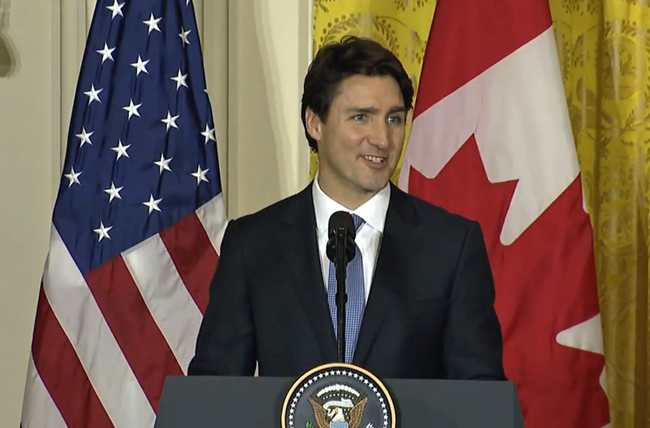

Trudeau’s hope of a quick resolution to NAFTA, to restore business confidence and certainty in Canada, will likely go unfullfilled.

WASHINGTON—A quiet power struggle over NAFTA has finally broken into public view, a tug-of-war within Washington between a faction seeking a quick conclusion and another urging lengthier negotiations, possibly spilling into next year.

The tension between those conflicting aims has existed as a quiet dynamic of the recent NAFTA conversations before this week, when it erupted into the open.

The Canadian government made clear which side it’s pulling for.

It made a public show of throwing its energy in with those seeking a speedy conclusion, in multiple meetings in Washington and New York, in public comments from Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and in two private conversations with President Donald Trump.

It has allies within the administration as evidenced by public comments this week by White House economic adviser Larry Kudlow and Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue, who both expressed hope for a conclusion.

Trump son-in-law Jared Kushner has remained publicly mum but has also made numerous trips across the street from the White House to assist negotiations at the U.S. trade headquarters.

But one powerful opponent of a speedy deal also made himself heard this week.

U.S. trade czar Robert Lighthizer, who has been reluctant to schedule rounds and is viewed as a quick-deal skeptic, stood his ground in that tug of war: “(We) are nowhere near close to a deal,” Lighthizer said in a rare public statement.

“There are gaping differences.”

Related: ‘Nowhere near close:’ U.S. rebuffs Trudeau’s hope for quick NAFTA deal

The struggle isn’t over. Conversations about wrapping things up are still happening on multiple fronts, according to people close to the talks. It also came up when Trump called the prime minister late Thursday, in what was described as a friendly phone call.

The reason the Canadians want a quick deal, as do some allies in the U.S., boils down to a desire for certainty. Trade instability has hit business investment in Canada, reducing it by a projected two per cent this year, and in the U.S. it has added to the compendium of woes clobbering farm states.

Trudeau this week publicly signalled the Canadian view that a deal is being held up for unorthodox reasons.

He suggested the main impediment to an agreement has little to do with any one industry and lots to do with Lighthizer’s insistence on weakening the agreement via a five-year sunset clause and stripping down dispute-resolution systems.

Trudeau specifically mentioned the sunset in a New York appearance, even mocking it with a real-estate metaphor designed to appeal to the president: Why would anyone construct a building, he asked, if the deal for the land could end in five years?

Lighthizer retorted with a statement that highlighted additional concerns—agriculture, intellectual property, online duties and several other issues.

Several insiders saw that statement as Lighthizer pushing back.

Trade lawyer and U.S. political insider Dan Ujczo said he believes it pits the trade czar against others—Perdue, Kushner, and Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin—and he suggests even the president is sympathetic to the idea of notching a quick win.

He read Lighthizer’s statement as sending a message that a deal now would fail to address numerous concerns, alienate those industries and constituencies left out, and cause a backlash against Republicans in a midterm election year.

Lighthizer spent years as a congressional staffer and knows the institution. Ujczo said he understands that members of Congress are wary of endorsing a deal that disappoints key industries and donors.

For example, negotiators have barely tackled the irritants of dairy, and pharmaceuticals.

“There’s not a member of Congress that wants to touch NAFTA right now,” Ujczo said. “Once you start putting agreement text out there there’s going to be winners and losers. And in an election year, the losers can make themselves heard.”

The Canadian case for a speedy conclusion is that it’s a pretty good deal now and it might not get better.

Trudeau and others argue that negotiators have practically resolved the biggest cause of the United States trade deficit with Mexico, supposedly the very reason Trump wants these negotiations—autos.

There is another fear from those pushing for a quick agreement: that greater delay means greater risk that talks fall apart. Some of the politicians involved now won’t even be around if this continues into next year, as Mexico will have a new government and the U.S. will have a different Congress.

Meanwhile, all three countries insist they’re prepared to keep talking. They just haven’t decided yet for how long. Ujczo expects one more push for a deal, then a slowdown next month for the Mexican election, and another try in 2019.

Here are some key flashpoints in the talks involving Canada:

- Autos: This is the sticking point countries have spent the most effort trying to solve. The U.S. wants to stem the loss of manufacturing jobs to Mexico. Canada broadly shares that goal. However, the issue has prompted some concern, and not only from Mexico. While the U.S. has significantly softened its earlier demands, it still wants 40 per cent of every car built in a high-wage jurisdiction; 75 per cent of all parts to be North American; and 70 per cent of steel to be North American. Critics of the plan say it could backfire: if auto-makers decide they don’t want to deal with all this red tape, they can just ignore NAFTA and simply pay the 2.5 per cent U.S. tariff on cars. Critics say that won’t create jobs—just more expensive cars, and less economic activity.

- Pharmaceuticals: It’s the stated goal of U.S. trade policy to make other countries pay more for drugs, so that foreigners shoulder more of the burden of research and development costs. The U.S. has a particular gripe with Canada: it’s reduced Canada’s ranking in an annual report card on intellectual property, partly over policy changes at Canada’s Patented Medicine Prices Review Board. The U.S. wants more transparency in how drug prices are set in Canada. Its industry is also pushing for greater ability to appeal pricing decisions. Such objectives place it in direct conflict with the Trudeau government, which wants to create a national pharmacare plan and intends to argue that its policy is consistent with that of President Donald Trump, who campaigned on controlling drug prices.

- Dairy: The U.S. has two problems with Canadian dairy policy. First, Canada limits imports and sets fixed prices under a supply-management system, and does the same for poultry and eggs. Second, Canadian producers who are protected from competition are at the same time selling surplus ingredients onto the world market for cheese-making, contributing to a global glut. The U.S. has demanded an end to these surplus sales, and also an end to supply management within 10 years. Canada’s counterpoint is that the U.S. engages in its own protections, supporting farmers during boom-bust cycles; it argues that Canada’s system at least has the benefit of being stable, and not requiring periodic bailouts. If past history is any guide, a middle-ground compromise might be possible: in agreements with Europe and the TPP countries, Canada opened up its dairy market by several percentage points.

- Dispute settlement: NAFTA is enforced by three main systems for settling disputes: Chapter 11 lets companies sue governments for unfair treatment, Chapter 19 lets industries fight punitive duties, and Chapter 20 lets countries sue countries. The U.S. wants to weaken two of the three, and entirely end Chapter 19. It’s a historically emotional issue for Canada, as Chapter 19 was the original make-or-break condition for free trade with the U.S.; it’s also been used to fight softwood lumber duties. However, some observers question the relevance of Chapter 19 today, as other forums exist for fighting duties. Take the spat against Bombardier, in which duties were overturned in the U.S. court system. As for Chapter 11, Canada has less of a historical attachment, although it’s extremely popular with those business allies in the U.S. fighting to preserve NAFTA. The Trump administration’s trade czar dislikes all these systems —Lighthizer sees them not only as a violation of national sovereignty: he argues that Chapter 11 helps companies do the dirty deed of outsourcing jobs. He argues that if companies want to shift plants elsewhere, the U.S. government should not be in the business of protecting their legal rights in, for instance, Mexico.

- De minimis: Americans are allowed to spend $800 online before they pay duties on a foreign purchase; Canadians can spend $20. It’s one of the lowest rates in the world. Lighthizer says it might not be necessary to match the U.S. amount, but he says that 40-fold difference is unreasonable. Retailers argue that shifting the de minimis level would fuel a commercial real-estate crisis, and disproportionately benefit American tech companies which enjoy economies of scale.

- Intellectual property: The U.S. complains about Canada’s border controls on counterfeit goods. It says it’s concerned that Canada doesn’t provide customs officials with the ability to inspect, seize, and destroy pirated goods moving through Canada to the United States. It complains that there were no known criminal prosecutions for counterfeiting in Canada in 2017, calling Canada an outlier among developed countries. It also bemoans what it calls excessive use of education-related exceptions to copyright laws, which it says have damaged the market for educational publishers and authors.

- Procurement: Canada’s aim is to increase companies’ access to public-works contracts abroad, expanding that access from federal contracts to state/provincial and local ones. Currently, subnational procurement rights are negotiated on a case-by-case basis. The U.S. has the opposite goal: It wants to limit the access Canadian and Mexican companies already enjoy at the federal level, restricted to whatever amount of contracts American companies win in the other countries.

- Sunset clause: One of the most controversial ideas of this negotiation. The U.S. has pushed for a clause in the deal that would cancel NAFTA after five years, unless every country agrees to keep it. Critics say this is a recipe for permanent uncertainty. They ask how a car company, for instance, is supposed to invest in all the assembly-line changes demanded in this deal, when the whole deal could be over in five years. They also point out that NAFTA already has a termination clause, which countries can invoke if they’re unhappy. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau ridiculed the sunset idea in a public event in New York. He used a real-estate metaphor and made clear he was addressing President Donald Trump: What developer would build a skyscraper on a piece of land, Trudeau asked, if access to that land was only guaranteed for five years?

- Professional visas: Canada wants to modernize the list of professions eligible for a NAFTA work visa under Chapter 16. The current list of jobs eligible for these visas is decades old, and features almost nothing for the tech industry. Companies complain this makes it hard to send their own employees to branches across the border. The U.S. has put up some resistance, as any expansion of work-related migration risks being wrapped into the heated U.S. immigration debate.