Swiss firm fires up world’s first full-scale plant to scrub CO2 from ambient air

by Cleantech Canada Staff

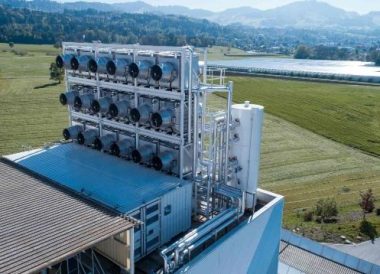

Climeworks uses an array of filters to pull carbon directly from regular air. The new plant is the first commercial-scale facility of its kind and can remove 900 tonnes of CO2 from the atmosphere each year

The company’s capture process draws regular air into collectors that trap CO2 in filters using a chemical process. PHOTO: Climeworks/Julia Dunlop

HINWIL, Switzerland—As global carbon dioxide emissions continue to hover near record levels, most governments, companies and organizations are taking aim at climate change by paring down on the amount of CO2 they release into the atmosphere.

One Swiss cleantech company is coming at the problem from a different angle.

Last week, Zurich-based Climeworks switched on the world’s first commercial-scale facility that pulls CO2 directly from ambient air. The plant was built on top of an existing waste recovery plant in Hinwil, Switzerland, and is capable of capturing 900 tonnes of CO2 each year.

Known as direct air capture (DAC), the company’s scrubbing technology works by drawing ambient air into the plant’s CO2 collectors. Once inside the collectors, the carbon dioxide in the air bonds chemically with a filter—trapping it—as the rest of the air passes through the filter and is released back into the atmosphere. To extract the captured CO2, the fully-saturated filters are then heated to about 100 C, allowing CO2 gas to be collected in a concentrated stream.

Climeworks says its filters can be used for several thousand cycles before they need to be replaced and that the Hinwil plant gets the energy it needs from excess heat generated at the waste recovery plant.

The plant is built on the roof of a waste recovery plant outside Zurich, Switzerland. PHOTO: Climateworks

“Highly scalable negative emission technologies are crucial if we are to stay below the two degree target of the international community,” Christoph Gebald, the company’s co-founder and managing director, said in a statement.

“The DAC-technology provides distinct advantages to achieve this aim and is perfectly suitable to be combined with underground storage,” he added.

While the CO2 stream from the Climeworks plant could be sequestered underground, the Swiss firm has struck a three-year deal to supply a local greenhouse with the CO2 it captures at the plant. The Swiss tomato and cucumber grower will release the CO2 into its greenhouses, helping to improve plant growth and boosting crop yield 20 to 30 per cent.

Quebec cleantech firm CO2 Solutions struck a similar deal to supply a nearby greenhouse with carbon dioxide captured at a Saint-Félicien, Que. pulp mill last year.

Along with greenhouse applications, the captured CO2 can be used to produce synthetic fuels or in the beverage industry. It can also be permanently sequestered, resulting in negative emissions.

The company did not release the cost of the new plant, but says its technology scrubs carbon from the air for less than US$100 per ton.

While it’s a step forward in the battle against ballooning carbon emissions, the new commercial-scale site is capable of scrubbing just a tiny fraction of global CO2 emissions from the air.

Capturing even a single per cent of the world’s CO2 emissions through direct-capture will be a major undertaking.

Still, Climeworks is aiming to achieve this ambitious goal by 2025. Gebald estimates that it would take 250,000 of the Hinwil plants to achieve the target, but insists such a scale-up is within the the global economy’s reach.

A similar, though smaller-scale project is underway in Squamish B.C., where Carbon Engineering is piloting another method for pulling CO2 directly from regular air. The company is aiming to produce ultra-low emissions synthetic fuel.

Though direct air capture can result in negative emissions, scientists have warned against pursuing the technology as an alternative to reducing emissions.

“Relying on big future deployments of carbon removal technologies is like eating lots of dessert today, with great hopes for liposuction tomorrow,” said Chris Field, a professor of biology and director of Stanford’s Woods Institute for the Environment.

In a recent piece published in the journal Science, Field and a number of colleagues argue that expecting negative emissions technology to be capable of reducing the impacts of climate change in the future could delay concrete actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions today.