Solar-powered Juno spacecraft arrives at Jupiter

by Alicia Chang, The Associated Press

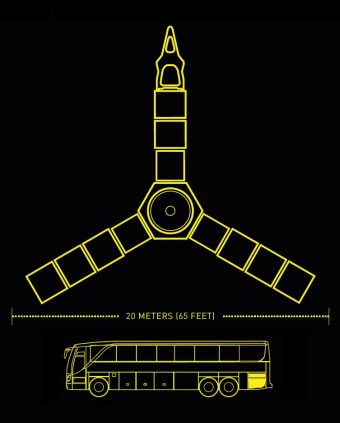

Running on three massive solar wings, which generate the energy for its instruments, Juno is the most-distant solar-powered probe ever deployed

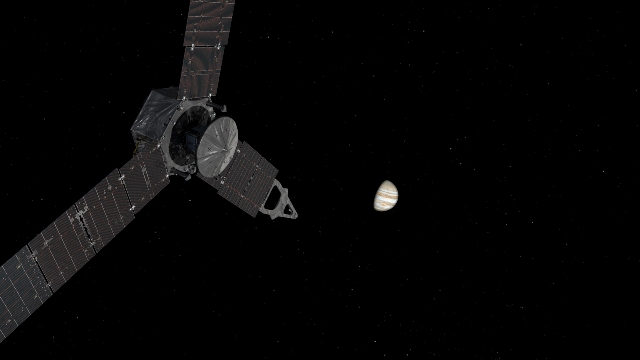

PASADENA, Calif.—Soaring over Jupiter’s poles, a NASA spacecraft arrived at the solar system’s largest planet on a mission to peek behind the cloud tops.

The final leg of the five-year voyage ended July 4 when the solar-powered Juno spacecraft fired its main rocket engine and gracefully slipped into orbit around Jupiter. Mission controllers celebrated when Juno sent back radio signals confirming it reached its destination.

“We’re there. We’re in orbit. We conquered Jupiter,” Juno chief scientist Scott Bolton said during a post-mission briefing.

In the weeks leading up to the encounter, Juno snapped pictures of the giant planet and its four inner moons dancing around it. Scientists were surprised to see Jupiter’s second-largest moon, Callisto, appearing dimmer than expected.

Three solar panels extend outward from Juno’s hexagonal body, giving the overall spacecraft a span of more than 66 feet (20 meters). Each of the panels are 9 feet (2.7 meters) wide, by 29 feet (8.9 meters) long. PHOTO: NASA/JPL-Caltech

The spacecraft’s camera and other instruments were switched off for arrival, so there weren’t any pictures at that key moment. Scientists have promised close-up views of the planet when Juno skims the cloud tops during the 20-month, $1.1 billion mission managed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

The fifth rock from the sun and the heftiest planet in the solar system, Jupiter is what’s known as a gas giant—a ball of hydrogen and helium—unlike rocky Earth and Mars.

With its billowy clouds and colorful stripes, Jupiter is an extreme world that likely formed first, shortly after the sun. Unlocking its history may hold clues to understanding how the solar system developed.

Named after Jupiter’s cloud-piercing wife in Roman mythology, Juno is only the second mission designed to spend time at Jupiter.

Galileo, launched in 1989, circled Jupiter for nearly a decade, beaming back splendid views of the planet and its numerous moons. It uncovered signs of an ocean beneath the icy surface of the moon Europa, considered a top target in the search for life outside Earth.

Juno’s mission: To peer through Jupiter’s cloud-socked atmosphere and map the interior from a unique vantage point above the poles. Among the lingering questions: How much water exists? Is there a solid core? Why are Jupiter’s southern and northern lights the brightest in the solar system?

“What Juno’s about is looking beneath that surface,” said Bolton of the Southwest Research Institute in Texas. “We’ve got to go down and look at what’s inside, see how it’s built, how deep these features go, learn about its real secrets.”

There’s also the mystery of its Great Red Spot. Recent observations by the Hubble Space Telescope revealed the centuries-old monster storm in Jupiter’s atmosphere is shrinking.

The trek to Jupiter, spanning nearly five years and 1.8 billion miles (2.8 billion kilometres), took Juno on a tour of the inner solar system followed by a swing past Earth that catapulted it beyond the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter.

Technicians at Astrotech’s payload processing facility in Titusville, Fla. stowing the second solar array against the body of NASA’s Juno spacecraft. PHOTO: NASA/JPL-Caltech/KSC

Along the way, Juno became the first spacecraft to cruise that far out powered by the sun, beating Europe’s comet-chasing Rosetta spacecraft. A trio of massive solar wings—each one 29 feet (8.9 metres) long and 9 feet (2.7 meters) wide—stick out from Juno like blades from a windmill, generating 500 watts of power to run its nine instruments.

Though producing a paltry amount of power orbiting Jupiter—equivalent to the amount required to run five standard light bulbs—the panels have the capacity to generate approximately 12 kilowatts to 14 kW of energy here on Earth. Jupiter’s significant distance from the sun accounts for the decreased efficiency of nearly 97 per cent.

In the coming days, Juno will turn its instruments back on, but the real work won’t begin until late August when the spacecraft swings in closer. Plans called for Juno to swoop within 3,000 miles (5,000 kilometres) of Jupiter’s clouds—closer than previous missions—to map the planet’s gravity and magnetic fields in order to learn about the interior makeup.

Juno braved a hostile radiation environment to reach Jupiter. Engineers prepared by housing the spacecraft’s computer and electronics in a titanium vault. Even so, Juno is expected to get blasted with radiation equal to more than 100 million dental X-rays during the mission.

Like Galileo before it, Juno meets its demise in 2018 when it deliberately dives into Jupiter’s atmosphere and disintegrate—a necessary sacrifice to prevent any chance of accidentally crashing into the planet’s potentially habitable moons.

—Associated Press writers Christopher Weber and Andrew Dalton in Los Angeles contributed to this report