Putting together an “efficiency gains” proposal

by James Reyes-Picknell

With a few calculated moves, the maintenance function could be the bedrock for big payoffs in sustaining productive capacity. Here’s how to build your maintenance business case

An often overlooked area where you can make relatively inexpensive improvements with potentially large payoffs is maintenance of your plant. In a recent case we determined the business case for making maintenance improvements for a company with $3.5 billion in revenues from six operating locations.

An often overlooked area where you can make relatively inexpensive improvements with potentially large payoffs is maintenance of your plant. In a recent case we determined the business case for making maintenance improvements for a company with $3.5 billion in revenues from six operating locations.

Maintenance costs were roughly $450 million. Analysis of the firm’s operating and maintenance performance measures revealed opportunities of $95 million in cost reductions and slightly more than $180 million in additional revenues for every 5% gain in throughput from operations. The effort to achieve these results was estimated at roughly $10 million over three years.

Those improvements came from a combination of efforts to improve the efficiency of maintenance execution and from improvements to the effectiveness of the proactive maintenance programs at the sites.

The estimated cost of making the improvements is $10 million in consulting support, plus what are likely to be minor changes to the maintenance management system and site efforts to execute the needed changes (already a sunk cost).

Is this your operation?

Most industries rely heavily on physical assets for production (factories, plants), product and/or service delivery (vehicle fleets, linear assets). Maintenance of those assets is usually the responsibility of a group of tradespersons, technicians and, occasionally, one or more engineers. Financially it is treated as a cost and pressed hard for cost reductions during the annual budget cycle. Despite being an enabler of production, it is treated as an expense and therefore something to be minimized.

Maintainers are often some of your most dedicated employees, working hard and long hours, often at odd hours when there are disruptions, to keep your operation running. Like the television character, MacGyver, they are creative and sometimes unconventional technical problem solvers who are all too often too busy with today’s problems to look ahead at how to avoid future disruptions.

If, like many companies, you’ve been on a “lean crusade,” then it is possible that you have cut too deeply into maintenance resources, leaving the department barely able to cope with ongoing breakdowns. If so, that same department very likely has no available capacity, and likely little capability, to shift from that reactive mode to being proactive and when asked, they will probably tell you they need more “resources” (that is, people). Today’s crisis will always trump tomorrow’s possibility and the “lean crusade” creates a department of “white knights” rushing to rescue the operation with little hope of ever truly becoming lean in anything but numbers of people.

How this impacts your costs and revenues

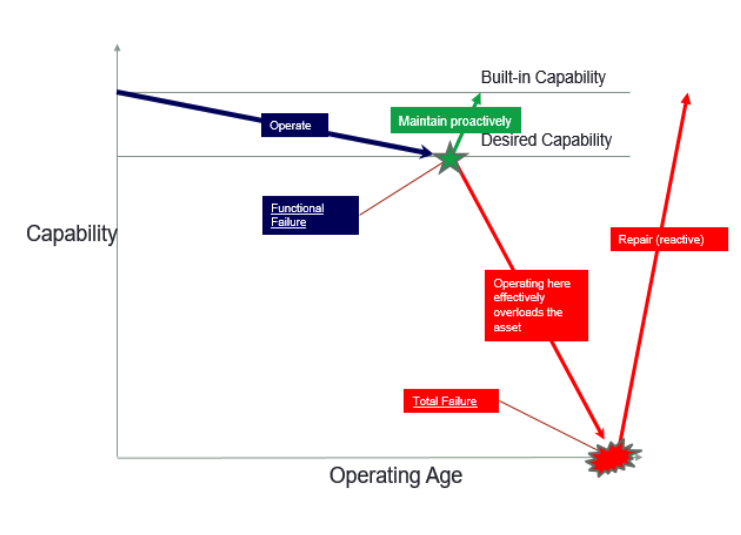

Proactive maintenance is the ounce of prevention that avoids the pound of cure (costly repairs to breakdowns). For work execution to be most efficient (consume the least labour and material) it must be thoroughly planned. Planned proactive maintenance is the lowest cost form of maintenance you can achieve. There are widely varying estimates of its cost relative to the costs of unplanned breakdown work, but the generally accepted rule of thumb is that it will cost one-third as much. That means it takes roughly one-third as long to carry it out (less downtime) and it consumes less labour and material. Conceptually you can see the difference in this graph of asset capability versus time (below). The proactive maintenance requires less time and effort and, because you are doing it proactively, you control its timing.

PHOTO: Asset capability versus time/James Reyes-Picknell

Good planning for maintenance is like the preparation done before hospital surgeries. Everything is ready for the job to start and the person doing the work is the right person for the job. The job is done quickly and done well.

Without planning the job will take longer. For example, if the correct parts are not available when the job starts, then the mechanic must identify the parts he needs, then acquire them (often with a long wait) before the job can really start. Those parts could have been identified in advance and before you scheduled the work, their availability could be assured.

If you work proactively you can time the job to minimize operational impact.

If you wait for the asset to fail (breakdown), then the asset determines the timing. Also consider that it will only break down when in use. That’s exactly when you don’t want to lose its capability. It will stop production and likely result in some scrap. The longer unscheduled and often unplanned repair results in more downtime than you really needed to incur.

Lack of maintenance preparation and proactive timing of work increases both costs and downtime which results in greater loss of revenues. It’s a double whammy.

How much does it cost you?

If you are in a worst-case situation where most or all of your maintenance work is “breakdown maintenance” (totally reactive), then a large part of your maintenance costs will be much higher (by a factor of three times) than they could be. The downtime from those repairs are longer than it needs to be and each hour of downtime has an opportunity cost associated with loss of revenue generation capacity.

Of course, not all of the breakdowns are worth preventing – some of them are merely nuisance work with no material impact on production. In well-designed maintenance programs, about 25% of the failures are actually allowed to occur, and those failures have no material impact on production, on safety or on the environment.

In the worst case – 100% reactive – you are likely spending twice as much as you should on your maintenance program and losing valuable productive capacity to the downtime associated with the breakdowns.

The fix

The role of maintenance is to sustain productive capacity. They do that through a combination of activities aimed at repairing breakdowns, preventing breakdowns, forecasting when breakdowns are likely to occur so that the consequences can be managed, and finding where installed backup and safety systems could fail to operate when needed. It helps a great deal if the equipment and systems they are maintaining are inherently reliable (a feature that must be designed in), and if operators use the equipment and systems properly and as intended without overloading them. Get those three aspects aligned and your costs will be low and operation highly reliable.

When we design a good maintenance program we are not really focusing just on failure avoidance, we are focusing on the avoidance of unwanted consequences of those failures.

A good proactive maintenance program combined with good planning and scheduling will reduce that reactive work. For each 1% of work that you shift from reactive to proactive, you will save about two-thirds of its cost.

By switching to a proactive approach you are also controlling the timing of when you do your maintenance activities. You will be acting before the asset reaches that point of functional failure (the green star in the graph). The asset will still be fully operational so you can time your work to coincide with a planned outage (typically on weekends or nights when production is down). You don’t avoid all of the maintenance work, but you do avoid the disruption, variability and loss of production that comes with breakdowns.

Determining the cost savings opportunity

Let’s say you have a Proactive Maintenance (PM) program but also suffer from excessive breakdowns. Your maintenance workload is 80% reactive (break then fix) and only 20% proactive. The excessive breakdown workload consumes your maintenance time and you are not getting all of the PM work done.

Your improvement program targets reduction of that 80% reactive work to 30% of the total workload. You will then be doing 70% of your work proactively – either PM work (preventive, predictive and testing) or proactive repairs of the defects those PM activities reveal. All of that proactive work can be scheduled to minimize production impact. Of the 30% that is still reactive, you have identified most of it as being repairs to equipment that has little or no production, safety or environmental impact.

To achieve that you will need a combination of efforts to improve planning, scheduling, work schedule discipline, work quality, and to identify the optimal proactive PM work to be doing. There are a few methods that will help with the latter, the most successful being Reliability Centered Maintenance (RCM) which should be done on your most critical assets.

The cost savings can be estimated using the 3 to 1 (reactive to proactive and planned) ratio of work costs.

We need to determine the generic “unit” of maintenance costs in your operation. A single unit is the cost of 1% of your work if it is proactive and planned. Each 1% of reactive work therefore, costs 3 units.

Let’s say your maintenance budget is $2 million and 80% of your work is reactive and 20% is proactive (as above). You want to shift that 80/20 split to 30/70.

Here’s how your maintenance budget is being spent:

- 20% costs 20 units.

- 80% costs 3 x 80 = 240 units.

- Total units are 260.

- Each unit is worth $2 million / 260 units = $7,692

Now let’s look at the future costs based on the new work distribution:

- 70% of work is proactive – cost is 70 units.

- 30% of the work is reactive – cost is 3 x 30 = 90 units.

- Total units are 160.

- Each unit is worth $7,692, therefore new budget is 160 x $7,692 = $1,230,720

The cost savings achieved is $769,280 annually.

Determining the impact of downtime

Unlike maintenance, which is actually very much the same regardless of industry, each operation will be unique. If you are producing diamonds or gold, your revenues per unit produced will be much greater than if you are producing cans of soup, cellphones or appliances. To estimate the opportunity for additional revenues you need to know the impact of downtime on revenues.

Many industries track delays, or production losses versus targets. This tracking is usually done in production control and monitoring systems and not in your maintenance system. Quite often the losses are attributed to a “cause” such as no feed, mechanical, electrical, operator error, start up, or change-over. Those causes are not very precise, but they are helpful. Obviously, maintenance cannot influence whether or not feed is available, whether or not operators do their jobs properly, or how often you must change over from one product tooling setup to another. We cannot count those as areas for potential benefit. But we can look at the mechanical, electrical and some of the startup losses.

If the startup follows a maintenance-related incident (such as a mechanical or electrical cause), then we can include it here. Avoid the maintenance-related problem and you also avoid the start-up losses that are associated with it.

Electrical losses should really be looked at a bit more closely too. Operators are most likely the ones who assign the loss categories in your tracking system. If they experience a breaker trip during operations they will often categorize the downtime as electrical. However, breakers trip when they are overloaded, not when machinery is being operated correctly. Some of those electrical problems may really be operator errors.

Examine your downtime records, determine how much of it is due to reliability problems and add up the time. Your finance manager should be able to tell you the revenue generated per hour of operation. If that’s not available, simply look at your annual revenues and divide by the number of operating hours in a year. For each hour of reliability (maintenance) downtime you’ve determined, then multiple by the dollars per hour of revenue potential.

In our example above, let’s assume that the shift of work from 80% to 30% reactive also means a 50% reduction in downtime actually performing maintenance. If startup losses account for another 5%, then you recover 55% of your downtime losses. Let’s say that last year revenues were $70 million and you had downtime losses related to maintenance causes of $20 million. Remember that much of your maintenance was reactive and caused disruptive downtime. Saving 55% of that will mean a revenue gain of $11 million – nearly a 16% increase in revenue and more than 14 times the value of the maintenance cost saving.

Those numbers are meant to be illustrative. In most industries, we actually do find that the revenue gains usually outweigh the maintenance cost-savings potential. As in the example at the beginning the article, the revenue gains were roughly 10 times the value of the maintenance cost saving.

Bottom line

Maintenance is often overlooked as a source of revenue while often being seen as a source of cost savings, yet without the needed investment in changing how things are done. As Einstein said, “we cannot solve problems using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them.” Before you can achieve different results you must change what you are doing, and before that you must change what you are thinking. Reframe your perspective on maintenance – it’s not a cost centre, it’s not a repair shop. Its function is sustaining productive capacity. Perhaps even go so far as to consider it a reliability department to shift the emphasis from fixing things after the fact, to the avoidance of business consequences.

James Reyes-Picknell, PEng, CMC is a professional business consultant who based in Barrie, Ont. He specializes in operational excellence and gains through maintenance and reliability improvements. Reyes-Picknell is a best-selling author of books on maintenance, reliability and physical asset management. In 2016, he was the recipient of Canada’s prestigious Sergio Guy Memorial Award for “outstanding contributions to the maintenance profession.” He is based in Barrie, Ont. Reach him at james@consciousasset.com or visit his website at www.consciousasset.com.