Are vaccines already helping contain COVID? Early signs say yes, but mutations will be challenging

by Maximilian de Courten, Professor in Global Public Health and Director of the Mitchell Institute, Victoria University; Maja Husaric, Senior Lecturer; MD, Victoria University, and Vasso Apostolopoulos, Professor of Immunology and Pro Vice-Chancellor, Research Partnerships, Victoria University

Over 130 million doses have already been administered worldwide. It's early days, but the signs are promising in places like Israel and the UK

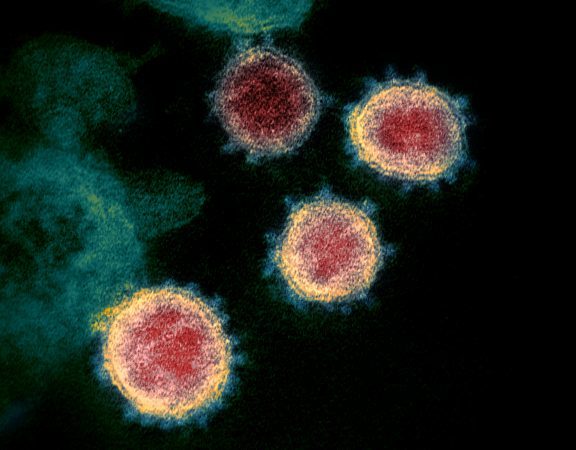

COVID-19 variants are on the rise.

Image: NIAID-RML

More than 130 million COVID vaccine doses have been administered worldwide already, according to the University of Oxford’s “Our World in Data” vaccination tracker.

Israel, the United Kingdom, the United States, the United Arab Emirates and China are leading this huge global effort.

COVID vaccines were initially tested and approved on their ability to reduce the severity of the disease.

However, the long-term goal of vaccination is to decrease infection rates and eliminate the virus.

Excitingly, early signs suggest vaccines are already helping drive down infection rates in some countries, including Israel and the UK.

In saying that, it’s early days, and some preliminary data suggest countries might have to update their vaccine strategies to deal with emerging variants of the virus.

Israel is leading the way

The US (43 million doses), China (40 million) and the UK (13 million) have administered the most doses in total.

However, these numbers don’t take into account population size, so looking at the number of doses injected per 100 people is more meaningful.

Here, the league table is currently topped by Israel, with around 67 vaccination doses administered per 100 people.

Almost 25% of the population are fully vaccinated with both doses. And all this in just five weeks.

Israel aims to vaccinate everyone over the age of 16 and reach at least 80% of its nine million people by May this year.

Reaching at least 70% of the population via vaccination (and/or natural infection) is needed for herd immunity for COVID, according to initial modelling by University of Chicago researchers in May last year.

However, given more infectious variants of the virus have emerged, we may need to vaccinate an even higher proportion of the population to reach herd immunity.

Infection rates are falling

So far, Israel is solely using the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine. Interim reports from the country suggest the vaccine rollout is linked to a fall in infections in people over 60 years old.

It can be tricky to separate the effects of public health measures such as lockdowns versus the effects of vaccination.

But because the fall is most pronounced in older people who were first in line to receive the vaccine, data suggest this is also partly due to the vaccine, and not just the country’s current restrictions. A team of Israeli researchers found larger falls in infections and hospitalisations after the vaccinations than occurred during previous lockdowns.

Only 0.07% of the 750,000 over-60s vaccinated tested positive for COVID, according to Israeli Ministry of Health data released last week. And only 38 people, or 0.005%, fell ill and required hospitalisation. The chance of testing positive for COVID two weeks after receiving the first dose was 33% lower than in those not vaccinated.

The UK is also showing positive signs

The UK has administered 19.4 doses per 100 people. Around 13.2 million people (or one in five adults) have received the first dose, and 0.5 million have received the second dose.

It’s currently using both the Pfizer/BioNTech and Oxford University/AstraZeneca vaccines in its rollout.

The infection rate appears to be decreasing substantially. The current daily infection growth rate is falling by between 2-5%, and the R number is estimated to be between 0.7 and 1 (an R number of less than 1 means daily new cases will decrease over time).

However, it’s difficult to determine whether these numbers are due to the lockdown or vaccinations. It’s too early to tell whether vaccines are slowing transmission, but the signs are encouraging.

According to data from the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine group, released as a preprint with The Lancet last week and yet to be peer reviewed, its vaccine is showing signs of reducing transmission. The shot was associated with a 67% reduction in transmission among vaccinated volunteers in clinical trials in the UK.

It’s early days, but authors of the study suggest the vaccine may have a “substantial” effect on reducing rates of transmission in the future.

In saying that, preliminary data suggest it offers minimal protection against mild or moderate illness caused by the South African variant.

What threatens the successful rollout of vaccines?

There are three main problems that might hinder the success of this global vaccination drive.

1. Vaccine development, manufacturing, distribution and delivery

The world’s population over the age of five is currently estimated at seven billion people. If we need to vaccinate at least 70% of them to achieve herd immunity, we need to reach around five billion people.

This is an enormous undertaking, so vaccine production and availability are crucial. Many countries face the massive challenge of producing or securing enough vaccines to immunise all their citizens.

Generally, wealthier countries that could afford to make advanced purchase agreements with vaccine producers — or who could manufacture a vaccine domestically — have been the first to start COVID vaccinations.

Unfortunately, partial vaccination of the world’s population won’t achieve herd immunity. One modelling study suggests if high-income countries exclusively acquire the first two billion doses without regard for vaccine equity, the number of COVID deaths could double worldwide.

2. Administering, monitoring, and reporting adverse effects

Vaccinating a large number of citizens quickly can’t be done with existing health institutions alone.

It’s urgent we enable alternative sites such as halls and sporting venues to be used as mass vaccination sites. We also need to allow a range of health professions such as medical students, public health officials and pharmacists to administer doses to help speed up the process.

And once vaccines have been administered, it’s crucial we monitor efficacy and report on any adverse effects, which will require additional resources.

3. Vaccine effectiveness and virus mutation

The effectiveness of vaccines can be hindered by mutations of the virus. COVID variants originating in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK have triggered huge concern worldwide.

There’s early evidence some of our current crop of COVID vaccines respond less effectively to certain variants, though most of these data are preliminary and are still emerging.

If vaccines become less effective, new vaccines will need to be developed either including a booster dose incorporating the region of the mutated virus, or reformulating existing vaccines to include the mutated strains.

This, however, isn’t uncommon — flu vaccines are required to be updated regularly in order to increase protective capacity against new mutated strains.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.