Canada’s new climate plan: Q&A about Bill C 12

Moving to net-zero emissions over a 30-year time frame means that Canada needs to start targeting reductions of 3% to 4% each year

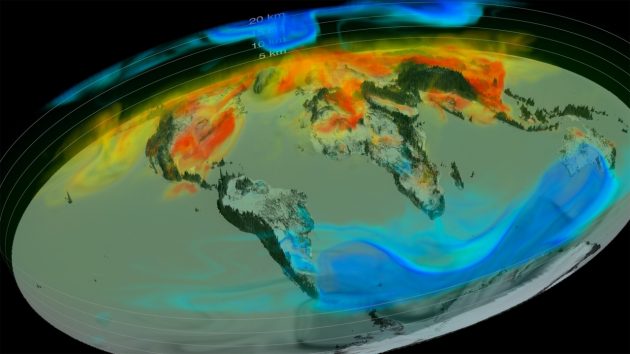

3D visualization of carbon dioxide n the atmosphere increases, decreases and moves around the globe.

Photo: NASA/JPL-Caltech

On Nov. 19, Environment Minister Jonathan Wilkinson unveiled what was billed as a “Net-Zero Emissions Plan.” What we got is most emphatically not a plan, but it is a piece of legislation that demands Canada set targets and develop plans that will get us to net-zero emissions by 2050.

The government hasn’t set any targets yet, or told us how we will get there. But moving to net-zero emissions over a 30-year time frame means that Canada needs to start targeting emission reductions of three per cent to four per cent each year. On the whole, Canadians emitted the equivalent of 729 megatonnes (Mt) of carbon dioxide in 2018, so we will need to reduce emissions by more than 20 Mt every year.

If we started to achieve these sorts of reductions now, in 2020, we would just about meet our current target, which is a 30 per cent reduction from 2005 emission levels by 2030.

How is this “climate plan” different?

Canada has a long history of setting climate targets and then missing them. One problem with our approach in the past is that we have treated the emissions problem like a series of individual, unrelated challenges.

We’ve had legislation that mandated proportions of renewable fuels to try to address transport emissions. We’ve had legislation to phase out coal use in electricity generation. We’ve introduced new programs designed to support new technologies and provide new energy options. We’ve thought of these programs in isolation, but not as part of a larger energy system.

Arguably Canada has only two policies that address emissions in a holistic fashion: Carbon pricing and the clean fuel standard.

Carbon pricing helps industry and individuals make cleaner choices, but our current pricing levels are too low to make more than incremental changes. The clean fuel standard will lower emissions by regulating reductions in greenhouse gas intensity for most fuels used in Canada, but it won’t come into force until 2022.

Can Bill C-12 succeed? One line within the text of the proposed legislation lends hope: sectoral strategies is an essential ingredient for success. What is needed now is a plan that clearly lays out the options for emission reductions in each major sector across the country.

Will there be dramatic cuts to oil and gas?

Two sectors will be the hardest to deal with: oil and gas production and home heating and cooling.

Oil and gas production plays an outsized role in Canada’s emissions (26 per cent) and in our economy (5.3 per cent of GDP in 2019). Some petrochemical refining processes are well suited to CO2 recovery and reuse, and there may be ways to burn fossil fuels without CO2 emissions.

But the majority of the research indicates that reducing greenhouse gas emissions in Canada’s oil sector will be almost impossible without corresponding reductions in production, and that significant reductions can only be achieved with significant cost increases.

It may be technically feasible to bring the oil and gas sector to net-zero _ but will it be financially viable? For this sector, Canada needs three interlinked strategies: an engagement strategy, to bring key provinces into decision-making; a diversification strategy, to apply the sector’s knowledge to new, low-carbon ventures; and a just transition strategy, to ensure that these changes don’t leave hundreds of thousands of workers behind.

What about buildings and houses?

While only 13 per cent of Canada’s 2018 emissions come from buildings, there are over seven million single-family homes across the country, along with thousands of apartment and condominium blocks and commercial buildings. Most of these buildings will need to be made much more efficient, switched to non-emitting technologies for heating and cooling, to meet the net-zero goal.

This means two key policy directions: a retrofitting incentive or subsidy to help landlords and homeowners pay for what will be very costly upgrades, and a technology push to get low-carbon options (like air- and ground-source heat pumps, or district heat) into our communities.

Are electric vehicles the answer?

Decreasing transportation emissions (25 per cent of 2018 emissions) will also be a challenge, although the technology to solve this problem is more advanced.

While vehicle fleets are regularly refreshed, it is critical that both light-duty and heavy-duty fleets shift towards the lowest-carbon options, likely electric vehicles for light-duty, and a combination of renewable fuels, hydrogen and electrification for heavy-duty trucks.

But really, road traffic must shrink to achieve reductions in transport emissions. Policies that support work-at-home options and better public transit will be essential.

Electricity production is another critical sector that must be addressed. Both renewable electricity and nuclear power will likely be required to offset reductions in the use of fossil fuels.

Large industrial emitters must also be tackled, although a number of technology options are being explored for critical industries such as steel and cement. In the area of renewable natural resources, there are great ideas to make agriculture and forestry more sustainable.

Are the provinces on board?

The provinces are central to Canada’s success in meeting its net-zero goals. They are responsible for electricity and for natural resources like oil, gas and coal.

Every emissions-reduction strategy that can be imagined relies to a large degree on electrification _ using more electricity for transportation and heat, as well as for manufacture and industrial processes. Every emissions-reduction strategy must also address the emissions from the production of, and use of, fossil fuels.

All provinces will carry a heavy load in meeting the goals of Bill C-12, but Alberta, Saskatchewan and Newfoundland and Labrador will likely pay more. The strategies we develop need to be informed by provincial perspectives if there is any hope of success.

As a piece of legislation, Bill C-12 gives the government an important tool. But we need a real plan now. We no longer have the luxury of making marginal, incremental improvements. We need three per cent to four per cent reductions every year, starting now. And that means getting serious with a wide array of synergistic strategies that _ acting together _ can take us to a net-zero future.

Warren Mabee, director, Queen’s Institute for Energy and Environmental Policy, Queen’s University, Ontario receives funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council, and from the Canada Research Chairs Foundation. This article is republished from The Conversation.