94-year-old lithium-ion battery inventor unveils new solid-state breakthrough

by Cleantech Canada Staff

Close to 40 years after co-developing the first lithium-ion batteries, John Goodenough is still in the lab and still innovating—this time he's working with a new type of electrolyte

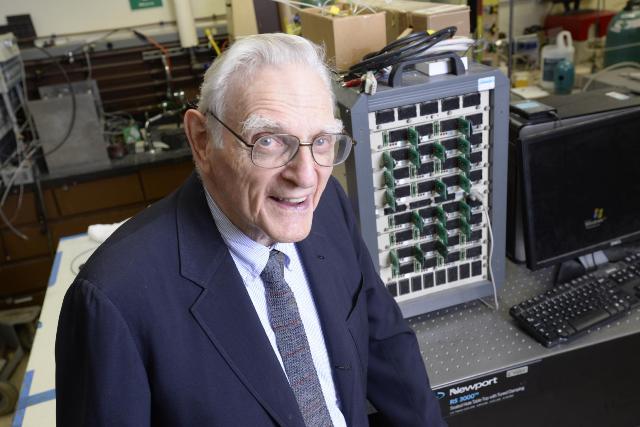

The 94-four-year-old researcher partnered with senior research fellow Maria Helena Braga on the project. PHOTO: University of Texas at Austin

AUSTIN, Texas—In his latest effort to push battery technology forward, a team led by lithium-ion battery co-inventor John Goodenough has introduced the first all-solid-state battery cells.

The 94-year-old engineering professor says the new solid-state design can never explode and holds three-times as much charge as lithium-ion batteries rolling off assembly lines today.

“Cost, safety, energy density, rates of charge and discharge and cycle life are critical for battery-driven cars to be more widely adopted,” Goodenough said in a statement. “We believe our discovery solves many of the problems that are inherent in today’s batteries.”

Foregoing liquid electrolytes, which transfer lithium ions between the anode and the cathode in typical lithium-ion devices, the new battery relies on solid-glass electrolytes—a technology collaborator and senior research fellow Maria Helena Braga first developed while working at the University of Porto in Portugal.

The new material eliminates one of the key issues with the electrolytes in lithium-ion batteries and allows the new device to be charged more quickly without the risk of a fire or explosion. Though it remains in the early stages, the development could lead to a new type of fast-charging battery that significantly outlasts lithium-ion.

Significant for Canada and other cold-weather countries, where lithium-ion’s poor performance in subzero temperatures has made electric vehicles a tough sell, the material operates well in temperatures as low as -20 C.

It could also be cheaper and put less strain on Earth’s resources.

“The glass electrolytes allow for the substitution of low-cost sodium for lithium,” Braga said.

Sodium is widely availability through seawater extraction and presents a cheaper, less environmentally-intensive solution.

In addition to the electrolyte, the new solid-state cells use an alkali-metal anode made of lithium, sodium or potassium—something that isn’t possible with lithium-ion devices. So far, the researchers have put the battery through 1,200 cycles and found the material increases the energy density of the cathode, translating to a longer cycle life.

Goodenough and Braga’s next step will be to work with battery manufacturers to test the new battery cells in electric cars and other devices.